Rappers share U.S. role models, but deliver a message styled for home

Asemahle Mphelo’s bed takes up half of his home. The other half is his production studio where he composes and records the raps he and his friends write.

Mphelo and his friends are quiet — shy, almost — until the beats start, and then, completely in sync, they bob their heads, close their eyes, and begin to rap, their expletive-laden lyrics similar to the ones used by the rappers they love so much: Kendrick Lamar, Lil Wayne, Tupac.

Kwaito, a style of hip hop that’s unique to South Africa, emerged in the early 1990s and coincided with Nelson Mandela’s release from prison and the end of apartheid. What separates it from hip hop is its delivery: kwaito lyrics are a mix of yelling, rapping and singing.

“We call ourselves new slaves...Slaves used to be in chains, but we now are buying these chains for ourselves.”

All three take their turns freestyling, but Mphelo is the real genius, coming up with poetic rhymes that are at times shocking and always thought-provoking.

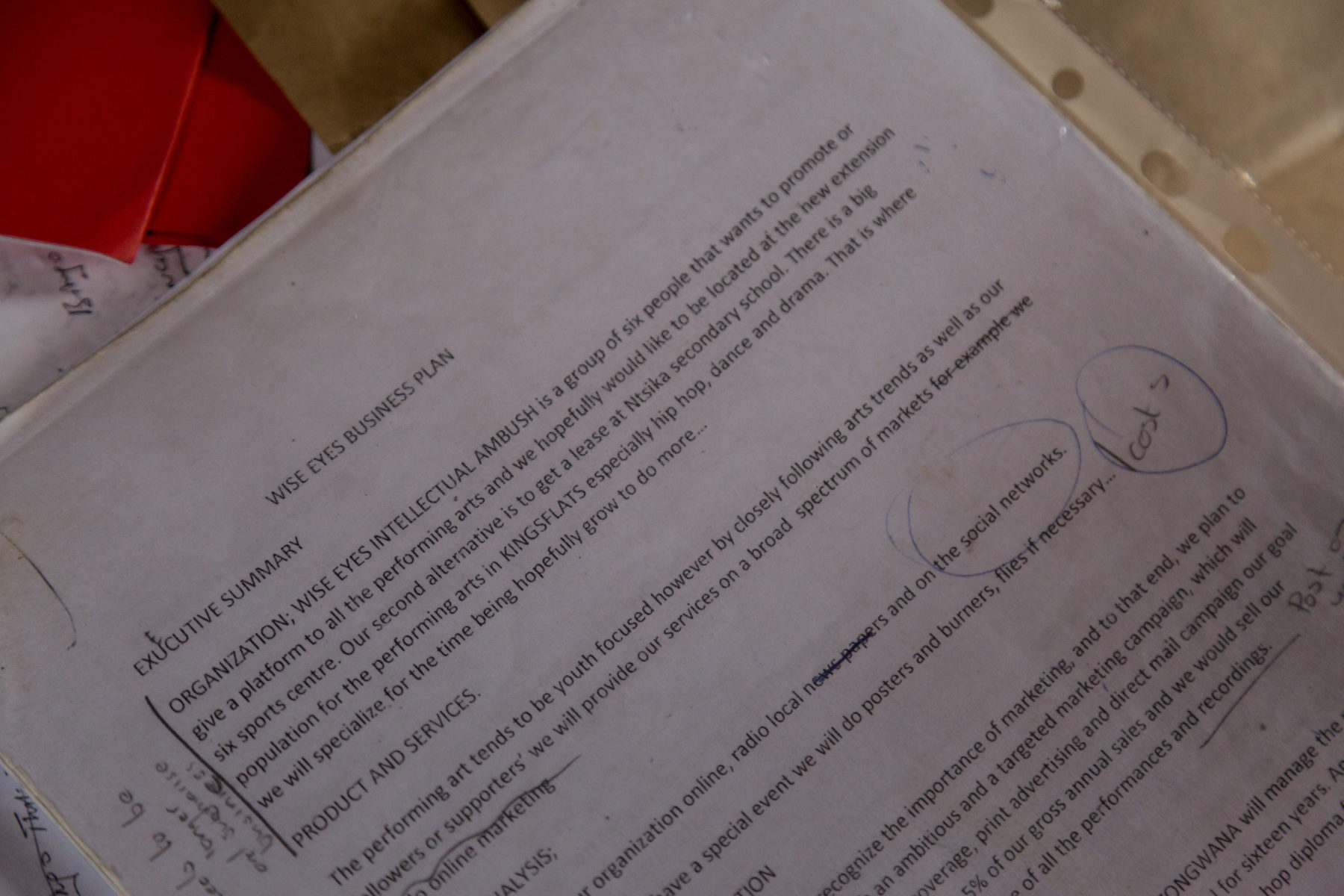

The inside of Siyanda Mphelo's home in Extension 6 in Makhanda, South Africa.

“We call ourselves new slaves,” he raps. “Slaves used to be in chains, but we now are buying these chains for ourselves.” He points to the silver necklace that’s hanging around his neck.

Mphelo is self-aware and fully realizes how others in his community view him, which is why he refers to his raps as “intellectual ambush.”

“In where we live, people always see us as these people who are junkies, people who come here in town and pickpocket people, so me, on the other side, I was also one of those people,” Mphelo said.

“I quit school for about three years and then came back after three years and got back to school. And I passed my grade 12, so after that, I realized no, I am intellectual, but you may never see that. And I will ambush you with what I am. You’ll be shocked.”

The inside of Siyanda Mphelo's home in Extension 6 in Makhanda, South Africa.

People wander in and out of Mphelo’s home. They peek their heads in to see what’s going on, and it doesn’t take them long to start bobbing their heads to the rhythm.

A man appears, seemingly out of nowhere, and joins in. “No more discrimination! No more segregation! It’s time for reconciliation!” he raps.

This man is Mphelo’s older brother, Siyanda, who founded Wise Guys, his rap group, in 1997, and who would later inspire his younger brother to write and rap.

The inside of Siyanda Mphelo's home in Extension 6 in Makhanda, South Africa.

Siyanda said Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur, along with Nelson Mandela and his presidency, greatly influenced him, and while his little brother considers his music to be intellectual ambush, Siyanda classifies his as a form of protest.

“We are protesting the human rights, the civil rights, because the government — there’s a lot of corruption up high, from Parliament down the ladder — so the resources don’t come to the people,” Siyanda said.

Siyanda Mphelo has not had an easy life, and he looks much older than his 34 years. He became addicted to drugs in high school and ended up dropping out. Later, he says his doctor diagnosed him with schizophrenia. His doctor told him he would need to take medication for the rest of his life, and he suggested that Mphelo write in a notebook. Mphelo took his suggestion, and be began writing poetry and raps.

The inside of Siyanda Mphelo's home in Extension 6 in Makhanda, South Africa.

The inside of Siyanda Mphelo's home in Extension 6 in Makhanda, South Africa.

“It’s the thing that healed me, you know? And got me off of the streets,” he said.

Today, Siyanda does not have much, but he still has his hope and his texts—he has saved everything he’s ever written. He lives next to his brother, so close, in fact, that the walls of each of their homes rattle and the ground floors vibrate when the other is playing music, and the two of them rap together regularly.

Siyanda Mphelo is also close with his childhood friend, Siyanda Futhufuthu, the other founding member of Wise Eyes and the person with whom Siyanda first started rapping in the late 1990s.

Futhufuthu is arguably the most successful of the three rappers; he recorded his first single, “Lomntana,” in 2004, which got airplay not only around Makhanda but nationally, as well.

“Why would I use drugs while I’m attending church? Because I found God in my life, so I have to change,” he said. “I had to stop doing what I used to do.”

Futhufuthu’s success, however, has been marred by his personal struggles with drugs. For many years, Futhufuthu was hooked on mandrax, a sedative-hypnotic drug that is highly addictive and incredibly easy to obtain in South Africa.

Futhufuthu said last year, he grew closer to God and eventually got clean.

“Why would I use drugs while I’m attending church? Because I found God in my life, so I have to change,” he said. “I had to stop doing what I used to do.”

His relationship with God has breathed new life into his music, and he now uses his raps to comment on the issues he believes plague his country today, including the mistreatment of women and children, drug abuse and poverty.

The inside of Siyanda Mphelo's home in Extension 6 in Makhanda, South Africa.

“This is nothing new to us,” he said. “It happens each and every day. It happens all the time, but it’s not right; that’s a fact, so I’m trying to warn people of these things. You can’t give up on your life because you’re suffering, because of poverty — no, you cannot do that.”

All three men see a different purpose in their raps, but what unites each of them is their common audience.

“When I’m writing these songs, I’m trying to put myself in someone else’s shoes because when I’m writing these songs, they’re not only about me,” Asemahle Mphelo said. “I’m singing these songs for the people in the community. So most of the time I look around me, the stuff that I always see each and every day. And when I’m writing, it’s like now I’m in that world. There’s nothing else that I can see than your pain or someone else’s pain.”